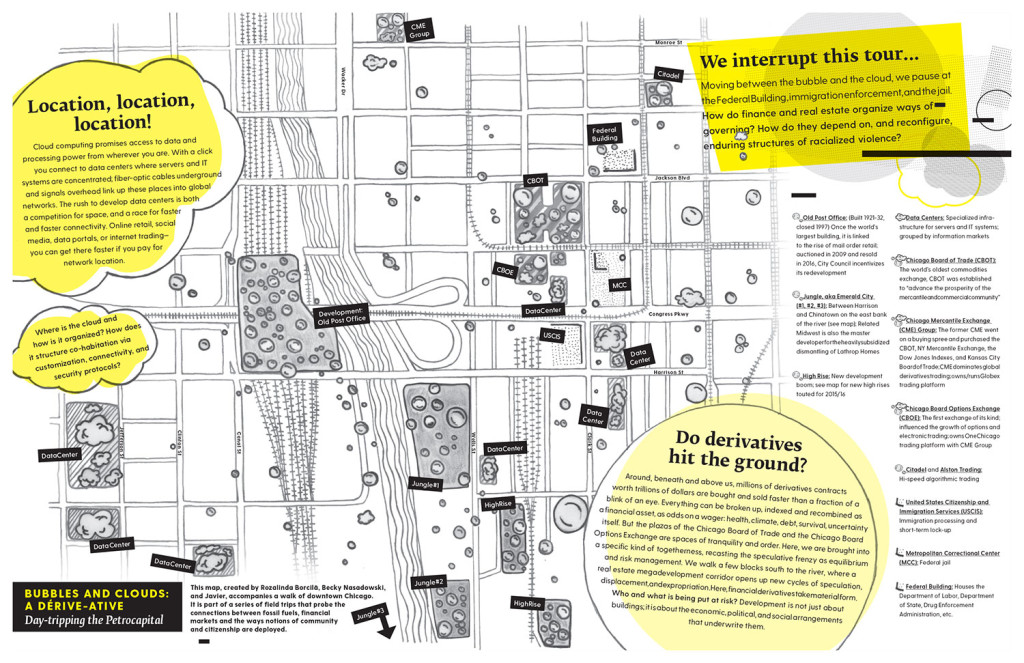

This text is part of a map accompanying a series of walks in the Financial district of Chicago, from the headquarters of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange southward across the opening acts of a real estate medagevelopment boom. Different groups of participants were assembled and invited to wander, trespass and research; the methods were improvisational and responsive to the differential mobilities of the participants, their relationships to property and law enforcement.

Walk description/invitation

Bubbles and Clouds – a dérive-ative through finance. On this field trip we strive for an analytic and sensorial interpretation of megadevelopment and fianancial markets. We take the pulse of the financial rituals, regulatory rejigging, technospatial competition and dream-making that produce the current cycle of real estate speculation and overbuilding booms. We hands-on demo the technologies of racial finance and collectively map the social logic of the derivative. Requirements: theorizing, body work and trespassing. (3-5 hours)

To download the full map click on image.

BUBBLES

A high rise development boom in the South Loop is targeting three plots of land on the east bank of the Chicago River, collectively known to squatters as La Jungla or Emerald City. This land was once the bottom of the Chicago River – when a deal between Railway interests, banks and mail order retail giants brokered the river’s relocation in a deal that took 10 years to negotiate and was finalized in 1926, 80 acres of dredge and landfill were born as real estate.

La Jungla remained undeveloped for over four decades. Tent cities have long self-organized and survived here, until recently. The last remaining tent city community is in danger of eviction: Related Midwest, who also spearheaded the heavily subsidized destruction of the Lathrop Homes public housing project, has partnered with General Mediterranean Holdings on a multi billion dollar redevelopment project for this site.

Cities subsidize the real estate market in many ways: land giveaways, zoning policies, pro-development planning commissions, public funding. While the official narrative is “demand”, cycles of overbuilding are spurred by excess financial liquidity and favorable regulatory climates. Flush from trading in “innovative” financial instruments, financiers partner with development firms seeking large-scale fixed assets. With Daley the Father, the city’s financial elites enacted an urban renewal program that consolidated the central business district and ghettoized the Black population. Daley the Son’s racialized development agenda included dismantling public housing and opening up the market for “mixed income” privatized development. The speculation on land and survival is deepening during the tenure of investment banker Rahm Emanuel, as private capital is increasingly connecting with “social programs,” and the space of daily life—rent, water bills, debt, health care—is reconfigured as an asset base for speculative trading.

Cultural and aesthetic practices are critical in the staging of urban redevelopment, in framing the problems, and in shaping the public imagination around solutions. In 2015, the Architecture Biennial hosted an exhibition and public debate about redeveloping La Jungla, framed as “a hole in the social fabric of the city.” None of the proposals acknowledged the site as already inhabited or addressed the economic calculations, partnerships, and instruments that assemble it as a real estate asset. The enclosure of La Jungla was accompanied by a symbolic emptying; its development could then be framed as an investment in “building community” and “civic infrastructure,” not as a contested field of makings and unmakings that manifest and reproduce uneven power relations.

CLOUDS

Picture this: an entire world of data and processing power at your fingertip, wherever you are. This is the promise of cloud computing. “You” as in the client: untethered, unencumbered, mobile, flexible, creative. Liberated. There is no body, only the touch: are you linkable, plug-in ready? Autonomy is connectivity, the ad reminds us, both customizable and contractual. In the next image we see the cloud as a sharing platform, an architecture of interaction and collectivity. Client as in aggregate of connections, cloud as in aggregate of protocols. Welcome to the community! No bodies, no friction, no flesh, no matter.

The cloud is made of time differentials: the time it takes to upload, to download, to share, to access, to execute, to connect. This time gap is a latency, a problem of speed, a measure of profitability in terms of network distance. Does this network have centers and peripheries? How is it organized? How are client collectivities elicited, routed, mined, incentivised? How does the cloud aggregate, and to what effects?

Today we linger where the cloud hits the ground and reshapes it. Cloud real estate is all about co-location, the competition for space in data centers housing servers customized to specific markets and linked in global networks shaped by a handful of developers. It also entails privileged access to connectivity across fibreoptic cables, laser and microwave signals. The cloud appears as informational and spatial competition, extraction, centralization, and (dis)possession.

The geography of the cloud has a material history shaped by previously existing pathways and infrastructures. It is path-dependent, evolving in relation to established rights-of-way [transportation corridors, energy grid and petroleum pipelines], the internet backbone, concentrated densities of economic power and capital flows. But the cloud also shapes space, pathways, relations. The race for informational advantage creates new public-private spheres, shifts regulatory climates, and tunes modes of governance to the imperatives of connectivity and security protocols.

UNDERLYING

After the subprime crisis of 2008, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) purchased the Chicago Board of Trade, the New York Mercantile Exchange, the Dow Jones Indexes and the Kansas City Board of Trade. The CME also moved the trading process from the pits (as seen on the news, the large rooms where traders yell at each other) to network environments that connect traders located at computer terminals around the world. Over 98% of futures trading is done from terminals linked through network platforms like Globex, owned and developed by the CME Group. A handful of data centers around the world contain the network’s main engines and servers, through which all electronic transactions must pass. As a result, CME now dominates global trading in derivatives and options; in 2016, this amounted to 3 billion transactions worth approximately 1 quadrillion dollars .

The CME Group’s middle school curriculum sets up the story of the derivatives market. Farmer Smith enters into a contract to sell 200 of his cattle [underlying asset] at a future date, for a price that he can “lock in” today. Farmer Smith gets some cash upfront [liquidity], which he needs to stay afloat [pay his creditors and costs, let’s say]; he also protects himself [hedging] against the risk of losing money if prices for cattle should drop too much. The counterparty [speculator] stands to profit if the price goes up in the future. Both parties are making a bet. This is called managing risk, or transferring risk from those who cannot bear it to those who can. In a world of uncertainty, it is speculation that creates both liquidity and stability—and this passes value on to you, the consumer [narrator takes a bite out of a piece of steak].

Every false story contains the possibility of its own undoing. The story of farmer Smith is haunted by the problems of labor and survival, and the delusion of money making money from money without the need for labor is troubled by the ways production and finance are integrated across global markets (remember the farmer’s credit obligations, or his operating costs?). How does financial speculation adjust production, the price of reproductive life, and the price of labor in the pursuit of competitive returns? Where/what are the systemic shock absorbers—who is unable to transfer risk?

The speculator has no interest in taking delivery on 200 cows; he does not trade in cows, he trades in price risk. The contract is a wager that will be bought and sold many thousands of times over, for profits many thousands of times greater than the value Farmer Smith’s cattle— and there are side bets on top of the initial one: I bet you 10 to 1 Farmer Smith’s future contract will be worth x amount less than first anticipated. You can bet on the price of beef falling, and pay a broker to write up an option (like an insurance) on the price of beef going up. The derivative logic exerts a coercive power on all of life. Every thing, it seems, must be reimagined as an underlying – broken up into a set of attributes, subjected to quantification and measurement, recombined across levels of fluctuation probability and subject to wagers between willing players. You can bet on the performance of future contracts you don’t own, or on thousands of slices of debt repayments bundled together in tranches according to default risk level. You can trade in weather volatility and you can bet on the survival of others. Bets on rent payments, water bills, health insurance contract payments, all are the basis for globally traded wagers.

As CME Group + Discovery Kids launched their school curriculum, Goldman Sachs introduced Social Investment Bonds (SIB): a financial instrument through which private capital invests in government entities to finance programs addressing “pressing social challenges.” The rate of return is risk-adjusted: it depends on achieving certain public policy benchmarks, thus trading in risk exposure to the performance of the state programs. The underlying asset in this case are the populations whose behaviors or performance are the targets of public social intervention programs: prisoners, poor people of color, “at risk” youth etc. The underlying asset for Chicago preschool program SIB is the performance of low income preschool children in relation to benchmarks indicating the need for future special education services – what is being traded is called exposure to special education financing risk. Given that the SIB contracts are issued by financial institutions whose board members also sit on the Commercial Club’s Education Committee, directly shaping CPS policy and assessment benchmarks, the rates of return are currently up to 50%, or $9,100 compounded at an annual rate of 1 percent for each child.

What are the conditions for the expansion of derivative logic across all areas of social life? Power resides in ownership of assets, but also in the capacity to redefine both asset and ownership as property relations, to organize transactions and informational advantage.