“With prophetic vision they beheld the completed canal bearing on its placid waters the products of the East, the West, the North, and the South; they saw the cities, villages, farms, and factories which would ultimately come into being along its course[1]”

Farmers and merchants began gathering in Chicago in the 19th century to trade. “There were merchants on every corner at harvest time, so the farmers would come in and talk to a merchant or two, but they were scattered all over the city,” says Fred Seamon, senior director of ag[ricultural] commodity research and commodity development with Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) Group… In 1848, a group of businessmen decided to centralize the merchants… “And immediately things got better because everyone knew what was going on.” Storage facilities were built so grain could be sold when it was worth more, giving the industry some price risk management. “You could lock in a price today, and no matter what prices did, you were protected. And that sort of evolved to futures”[2]

If you live in Chicago, you might recognize these passages as parts of a powerful and pervasive origin story. It narrates the birth of a calculative logic, a city and a settler social order that come to be understood, felt and lived as a world. We don’t always hear this story articulated explicitly, and yet everyday life is saturated with it. And precisely when seeming to disappear, it animates what Mark Rifkin has called a settler common sense, an “embodied set… of sensations, dispositions, and lived trajectories” that orients action in the “field of possibility” constituted by settler society[3].

The creation story conjures a human world emerging in the image of a financial ritual that Seamon names simply “futures”. Although he is referring to a specific financial calculation called agricultural futures, a type of derivative trading first organized at the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) in 1848, the slippage between futures as a logic of capital accumulation, and futures as referring more broadly to settler futurities, is an important one that I will take at face value.

In finance, derivatives – such as futures, options or swaps – are contracts akin to a wager. The wager is based on an initial “thing”[4] (commodity, financial instrument, index etc), known as the underlying asset or simply underlying; the value of the wager is derived from calculating the odds on how a certain attribute of that thing will fluctuate in the future. The most-cited example for defining derivatives is precisely the one Seamon gives, which holds a special prominence in narratives about Chicago’s greatness: agricultural futures. In this example, the underlying is grain, and the attribute that fluctuates, becoming the subject of the wagers, is its price. Traders of futures contracts do not take possession of the underlying; instead they buy and sell contracts for specific prices of that asset at specific dates. In our example, traders do not buy and sell grain, they buy and sell wagers on changes in its future price.

Dancer and sociologist Randy Martin has analyzed the ways derivatives are not merely a financial calculation, but a social logic[5], a process of disassembling, dispersal and reassembling that exceeds what we think of as the realm of finance proper and instead reorders the spheres of economy, polity and culture. Other scholars have explored the coercive force exerted by the derivative logic, so that everything in the human and more-than-human worlds becomes subject to being remade as underlying: broken up into a set of attributes, subjected to quantification and measurement, aggregated and then cut into tranches across levels of risk such that even the smallest differentials and fluctuations become opportunities for high-stakes wagers. You can bet on the performance of future contracts you don’t own, or on thousands of slices of debt repayments. You can trade in weather volatility and you can speculate on the survival of others.

But futures and derivatives, as a social logic and as financial calculation, have to be built. I collaborated closely with Brian Holmes on an art/territorial research project in which we tried to trace the physical excavations and extractions, forms of law and dispossession, the transformations of territory and the organization of capital that are the origin of Chicago and/as precisely this calculative logic. We called our project SouthWest Corridor NorthWest Passage.

Formally, it consisted of a website, map archive, series of experimental videos, interpretive texts, concept maps and exhibition. Our investigation followed the emergence of a trade corridor that runs SouthWest from the CBOT linking the financial district of Chicago with Kansas City, the Mexican port of Lazaro Cardenas, Panama and from there to ports in China. We were looking at local geographies of global finance, trying to grasp the patterns of flow linking canals, rail yards, warehouse districts, detention centers, real estate and financial logics. We developed a program of learning walks, inviting people to traverse the corridor with us — to touch the machinery of capital circulation and feel its pulse, to understand, as Brian likes to say, its metabolisms.

I am revisiting some moments of that project not to trace our findings or modalities, but to retroactively probe some pathways beyond it. In centering the settler-colonial narrative, or in storying from its perspective, we risk reproducing the violent erasure of Indigenous histories, peoples, social and legal orders that have existed here since time immemorial; we also risk reinforcing the myth of indigenous disappearance, normalizing settler worlds, jurisdictions and futurities. But this centering is here intended as a tactical and self-conscious move that tries to confront the peculiar operations of the common sense of settlerness – the ways we are implicated in the exertion of settler authorities over Indigenous peoples and territories through everyday experiences of non-relation, “a perceptual engagement with places, various institutions, and other people that take shape around policies and legalities of settlement but do not specifically refer to them as such”. This relation of non-relation is how settler colonialism becomes reproduced through sensations, dispositions and inclinations which “saturate quotidian life but are not necessarily present to settlers as a set of political propositions or as a specifically imperial project of dispossession”. I center the settler creation story in order to unnerve it; from here, my view is skewed towards the unresolved urgencies of building embodied acknowledgements of our co-implication in its reproduction, and searching for ways to thinkfeel beyond and against the worlds it animates.

NorthWest Passage

Back to our little project. From the perspective of colonial capital, the origin of the origin is the NorthWest Passage, an oceanic route conjured by European mapmakers beginning in the 1500s. A watery passageway to the China Sea and the riches of the Orient. In Brian’s words: “The imaginary figure of the Northwest Passage is the founding image of circulationist desire. It’s all about open water – or at least, it’s about liquidity.[6]” Colonial expansion across the Western Hemisphere in search for the passage, and the attendant representations of imagined journeys, speculations of what will be, anticipate the passage and also construct it.

In 1673, the search for the Northwest Passage brought the first colonists to what would later become Chicago. French settlers Jacque Marquette and Louis Joliet, together with five Métis voyageurs, set out from the French colonies in today’s so-called Canada. Instead of finding the Passage, they stumbled upon a great river flowing South, the Mississippi, and upon their return journey became hopelessly lost in a swamp. They were rescued by Indigenous people who guided them across a maze of shallow and shifting waterways. What the French colonists “discovered” was that it was possible to navigate by canoe from the Mississippi all the way to the Great Lakes with only a very short portage (from the French portager, to carry – in this case, to carry canoes that get stuck in the mud). Upon return from their failed voyage[7], Joliet would boast of their success and of the strategic significance of the expedition: this is because, he projects, digging a relatively short canal across the portage could be the key to the continent, making it possible for canoes, heavy with imperial commodities and armies, to travel from French colonial holdings to the North all the way to Louisiana and the Florida territories to the South. Such a canal would connect the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi and the Golf of Mexico, inaugurating a global watery trade route under the control of the French.

For the French and soon the British, the dream of a canal across the portage fuelled the will to subdue the swamp. Over more than one hundred years of rivalry, imperial sovereignties were proclaimed, but despite military, trade and diplomatic campaigns, despite triggering and arming intertribal warfare among Indigenous peoples as a proxy to inter-imperial competition, despite unleashing diseases and extractive economies that depleted ecosystems and pushed Indigenous peoples into forced migration across the Great Lakes, control over the portage eluded both the French and British, due to Native resistance and the agency of the wetlands itself.

The United States claimed the portage in 1787 in the organization of its first territorial jurisdiction. Although the westernmost boundary of the newly created sovereign remained far to the East of the wetlands, the Northwest Ordinance claimed from the British a zone of safe passage for American traders along the “navigable waters leading into the Mississippi and St Lawrence, and all the carrying places between”. This claim already envisioned a future canal and the territorial expansion of the Unites States West of Lake Michigan. It also emerged directly from forms of British colonial occupation that had been developed in the Eastern colonies, which involved producing land-based property regimes and exerting them along navigable waterways.

The Native wetland was known by many names and was home to Anishinaabe Nations (including the Niswi-Mishkodewin, The Council of Three Fires: Ottawa Ojibwa and Potawatomie) as well as the others such as the Miami, Illinois, Menominee and Ho-Chunk. The swamp, drained and transformed into parcels of dry settler-owned real estate traversed by a deep canal, would become Chicago. But how did this happen? How did settler jurisdiction become inscribed upon Native wetlands? Portage does not become corridor at the mere ritual of possession. And wetland does not become settler metropolis as an inevitable process, though narratives of colonial conquest over “unproductive” territories suggest otherwise, though the rigid contours of a canal cut out of bedrock suggests otherwise. The business of establishing colonial jurisdiction links the legal apparatus of sovereignty with property-making and war.

Over three decades of military campaigns and treaty-making, the US sought to intensify indigenous dispossession, increase settlement and secure its control of the region against competing imperial interests and Indigenous peoples. In 1803 the US erected a fort to defend its interests in the future canal zone; it was thoroughly sacked by Potawatomie warriors in 1812. British and American competition over the region drew multiple Native nations into the War of 1812. Between 1809 and 1813, Shawnee leader Tecumseh organized an anticolonial alliance throughout Great Lakes (also recruiting from among the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, and Osage). The allied rebellion was defeated in 1813.

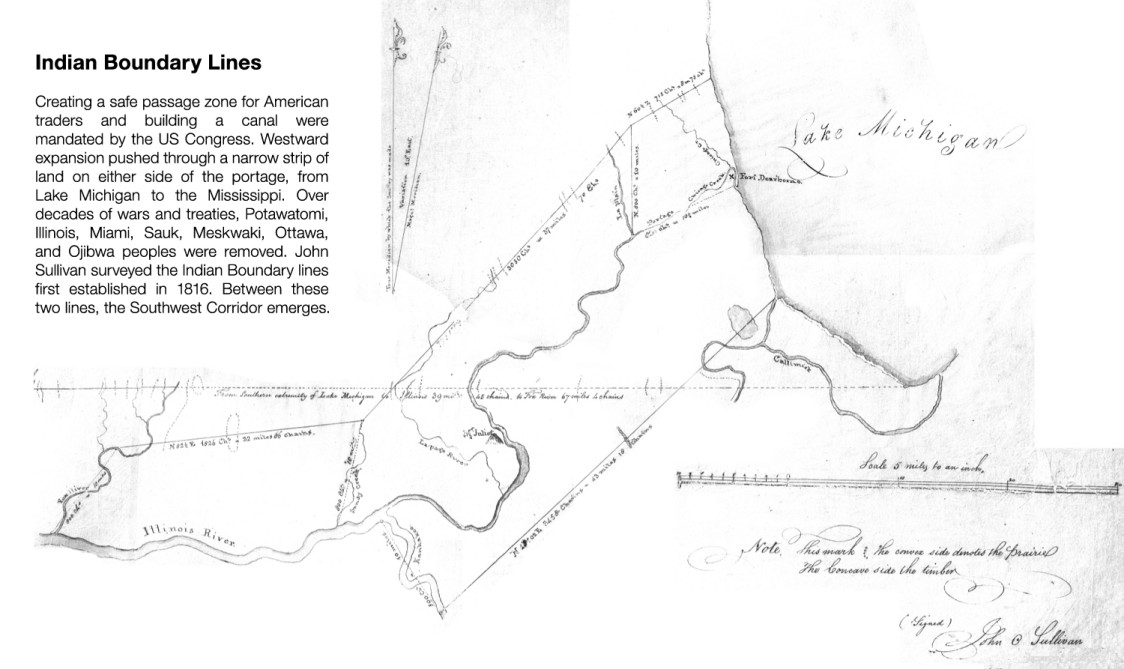

In 1816, in preparation for draining the swamp, the United States formally extinguished Native title in the canal zone by forcing the Niswi-Mishkodewin into the Treaty of St Louis. Two years later, surveyor John Sullivan traced two Indian Boundary Lines, marking a future canal zone to be emptied of Native inhabitants. The area was still only sparsely settled, and the settler nation was cash-hungry. So the future cities of Chicago and Ottawa were imagined in this zone and surveyed or “platted” in 1829 to create saleable future property. 300,000 acres were granted by the federal government to a newly formed Canal Commission, to be sold in order to raise the capital for canal construction[8] — future sales of future dry lands would be used to generate money in the present.

Over the next decades, various financing instruments were experimented with. Promissary notes or certificated of indebtedness were issued, with values and rates of return based on calculations of future income: primarily, future land sales (expected to appreciate in value exponentially), as well as future tolls and rents extracted from monopoly over what would become a major continental and global transport route for agricultural commodities – grain, as well as slave-produced sugar and cotton.

Mediated by this utopic fantasy, newly-created future property in land (an illiquid asset) was to be converted into stocks to be traded on global financial markets in the present (tradeable securities). But the present was not settled; it remained a Native wetlands, an entire world of human and more-than-human agencies in relational dynamism with land and water. The westward expansion of imperial capital might once again sink in the mud. To alleviate fears that the future envisioned by the financiers would not come to pass, the federal government had to mitigate against the risk posed by Indigenous bodies, ontologies, lifeways and legal orders. Securitizing a canal zone was predicated upon exclusionary violence.

The US military sought to crush ongoing Anishinaabe, Sauk and Meskwaki resistance and impose removal. During this time Makataimeshekiakiak (Black Hawk) understood the treaty-making process as reflecting and encoding the general disregard of the United States for Native forms of governance and legal systems. He built an alliance to deny the validity of the treaties upon which the current status of lands considered “ceded” in so-called Wisconsin and Illinois was based[9].

The military defeat of Makataimeshekiakiak and the massacres of his people in 1832, coerced treaty-making, and the enforcement of Indian Removal policies were decisive in pumping liquidity into the canal zone, fueling an invasion of settler populations and unleashing a real estate boom into the swampland. Securitizing the canal zone also carved out forms of territorial jurisdiction (a state, counties and municipalities) so as to underwrite the speculative economy making it all possible. Many different types of debt instruments were issued, traded, and reissued – promissary notes that were not mortgages on individual property, but instead represented projections of aggregated future profits that could be sold (traded) in the present, akin to mortgage-backed securities. This process of bundling and securitization was more attractive to investors than owning the mortgage on debt of individual parcels; still, the value of future sales, tolls and rents (the bond collateral) remained uncertain and speculative. Financiers continued to demand ways to hedge against the risk of individual loss, and to guarantee return on their investment. In 1835 the state of Illinois stepped in to pledge its credit and good faith for the repayment of Canal Comission bonds (which means its capacity to collect future taxes), making canal stocks marketable securities. These were the boom years.

Then came the bust. In 1842 the state of Illinois was on the verge of financial collapse, unable to keep up with payments on interest; the State Bank crashed. This was a financial crisis fueled by overspeculation in securities markets; the solution was to make the state more amenable to settlement and more “investable” . Legislators, who were also canal speculators, argued that a completed canal would “bring larger revenues to the treasury by increasing the basis of taxation, first, through the raising of property values by the capitalization of the diminution in transportation charges; and, secondly, by making the state a more attractive place for settlement and investment … The increased land values resulting from the opening of the canal would also enable the state materially to diminish the burden of the debt by liquidating a large portion of it through the sale of canal lands. In short, the difference between a completed and an uncompleted canal meant the difference between a solvent and an insolvent state”[10]. East Coast bankers and speculators, heavily invested in the Chicago real estate boom, negotiated new financing deals with British colonial magnates Magniac-Jardine&co and Barings Brothers. The cash started flowing again.

The SouthWest Corridor Northwest Passage website considers the significance of this story, in its full sequence: “the inscription of the Indian Boundary Lines, the expulsion of the indigenous people, the creation of private property, the speculation on its future value, the projection of infrastructure to produce that value, the subscription of debt to realize the infrastructure, and finally, the engagement of the state to guarantee the repayment of the debt in the wake of financial collapse. What is ultimately produced is the guarantee, the creditworthiness, the bankability of the state of Illinois, which is intimately related to the war-making capacity of the federal sovereign. As we looked deeper into the documents, the maps, the testimonies, the ruins and the remnants and the successive pathways that have been erected on top of them, we began to suspect that the story of the canal expressed and consolidated this inner logic of imperial capital, encrypted at its point of origin”

The processes that made possible the completion of the canal in 1848 also made possible the opening of the Chicago Board of Trade that same year. The Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) was the first grain futures exchange of the United States, erected by speculators who anticipated the flows of grain that would be brought in by the canal, and pooled in grain storage facilities alongside it called grain silos or elevators. These silos functioned as storage and also became a kind of banking system, converting seeds into standardized, abstract values, which could in turn form the basis for trade-able securities. The CBOT standardized grain futures contracts in terms of the quantity, quality, time in future (1 month, 3 months, etc) and place of delivery– only the price varied. Thus, farmers would take grain to storage in the silos; for each standardized quantity, the farmer would receive an elevator ticket (receipt), which functioned as a kind of money. The farmer could sell these receipts to traders who in turn would use them to buy and sell futures contracts though open auction at the CBOT. These contracts could be traded, bought and sold many times over before the delivery date, reflecting traders’ bets on future price fluctuations based on current patterns. This is the origin of what we know today as the global futures market, which the CBOT dominated until it was bought by its former rival, the CME Group in 2006. In 2018, the CME Group, where Fred Seamon is senior director of ag[ricultural] commodity research and commodity development, became the largest derivatives exchange on the planet.

The financial ritual by which projected future profits become made available in the present is called capitalization. Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler consider capitalization to be the decisive moment in the organization of global capital circulation[11]. They theorize it something like this: future earnings are estimated based on a set of agreed-upon current calculations, information and projections; this future value is discounted, which means subtracting a “premium” that calculates this projection as a risk (ie the future earnings or value of the asset might be affected by unforeseen factors). This produces a value that can be operated upon, or traded, in the present. When we say that something becomes capitalized, this is not the same as saying it was capitalized upon — becoming capitalized means becoming subject to the financial ritual of capitalization. It is what Nitzan and Bichler refer to as a process that creorders – that remakes the world in its own capitalized image.

For Chicago to come into existence, native wetlands had to be capitalized. As for the Northwest Passage, it is opening up right now with the climate change-induced melting of the Arctic Circle.

Is capitalization is creation story of the settler colony? Are we merely living projections of the future fantasies of the financier ancestors?

Living our Ancestors’ Utopias

Before Chicago, the wetland was traversed by a continental divide – a shallow rise that ran across it from North to South. Rivers to the East of the divide flowed into the Great Lakes and from there to the Atlantic. Rivers to the West flowed to the Illinois, then Mississippi and eventually the Gulf of Mexico. The same with rainfall. The first canal cut across the divide. Within two decades of its completion, it became an open sewer, pouring all of Chicago’s waste into Lake Michigan, the booming city’s only source of drinking water. This lead to deadly outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. To avoid immanent collapse, the city built a second canal in the 1890’s alongside the first one – deeper, wider and connected to pumping systems that would in effect reverse the course of the waterways and erase the continental divide. The first canal is buried under concrete and no longer visible at the location of its origin; the canal in the images here, and the canal of our walks, is the second one, euphemistically named the Sanitary and Shipping Canal. Local Anishinaabek have named it Zaaga’amoo-ziibiikaadeng (Defacation Canal). Hydraulic re-engineering has transformed lands and waters into a giant toilet, using Lake Michigan as a reservoir from which to flush Chicago’s shit down the Mississippi and into the Dead Zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

Native scholars and elders interpret the deliberate destruction of the wetlands as an ecological and even “climatic move” of settler colonialism[12] and theorize what settlers and Europeans call the Anthropocene as rooted in colonialism[13]. Kyle Whyte, Potawatomie philosopher and scholar of Indigenous Climate Change Studies, explains that colonialism “has always involved a terraforming that tears apart … the ‘flesh’ of human-nonhuman-ecological relationships”. From this perspective, Indigenous peoples and settlers are positioned differently in relation to climate change: whereas settlers are only now being affected “by the seismic waves of massive ecosystem transformation that began over 500 years ago”, Indigenous peoples have already suffered forced ecological dislocation and “away-migration” that destroyed partnerships with thousands of species and ecosystems. Indigenous peoples “have already been living in what our ancestors would have understood as dystopian or post-apocalyptic times[14]”. Settlers, however, deny the extent to which they have been living or fulfilling their ancestors’ utopias. He goes on to quote Lawrance Gross: “Just as importantly, though, Indians survived the apocalypse. This raises the further question, then, of what happens to a society that has gone through an apocalyptic event?” Reflecting on the present from the perspective of the ancestors provides Indigenous peoples with guidance on living under post-apocalyptic conditions; furthermore, actions in the present are “cyclical performances”, guided by “the desire to be good ancestors ourselves to future generations”.

Native scholars and activists have noted the extent to which settler societies have become interested in Indigenous cultures, philosophies and knowledge systems insofar as they contain important teachings about ecological change that can be extracted to help supplement settler climate science or manage fears of ecological collapse. Many Indigenous communities have developed practices in response to these extractivist tendencies. Anishinaabeg scholar Leanne Simson summarizes: “it is not enough to recover certain aspects of Indigenous Knowledge systems that are palatable to the players in the colonial project. We must be strategic about how we recover and where we focus our efforts in order to ensure that the foundations of the system are protected and the inherently indigenous processes for the continuation of Indigenous Knowledges are maintained.” Institutionalized forms of ally-ship and inclusion of Indigenous identities, cultural forms and knowledges often dis-remember Indigenous land claims and disavow their own implication in ongoing processes of indigenous dispossession. Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang have argued that decolonization cannot be merely a metaphor. Indigenous ecology educators and activists Janie and Fawn Pochel reiterate this position whenever invited to speak in the context of University symposia or progressive art exhibitions on ecology, the Anthropocene, or decolonization now proliferating in Chicago. When asked how they see native/non-native relationships, they consistently respond We would like our land back. I have repeatedly witnessed these exchanges, and have seen how this answer was dismissed as lacking complexity or as a myopic refusal to deal with the critical urgencies of extinction facing us all. This touches upon what Ka͞eyes-Mamāceqtawak (Menominee) scholar Ena͞emaehkiw Wākecānāpaew Kesīqnaeh calls an “existential dread that cuts a deep path clear across the entirety of white civil society[15].“ He goes on to explain: “Ongoing accumulation by dispossession is so deeply fundamental to the material basis, and attendant ideological outgrowths, of settler society that a call for even a small fraction of the bare minimum of decolonial justice—the return of what was taken from us—is interpreted as a clarion call for some kind of white genocide (and in this, the fear of white genocide, the circle between the white left and the white right becomes complete)”. He addresses the forms of allyship, interest, acknowledgement, apology or symbolic recognition that operate as a kind of disavowal, what Tuck and Yang have called “settler moves to innocence”. He also pushes back against the ways settler engagements with extinction become a way to reproduce the displacement of the geopolitics of indigenous sovereignty. “Reconciliation, decolonization, territorial acknowledgement, confession: none of them mean anything without the repatriation of our lands to our sovereign nations. Further, it is not for a radical Indigenous decolonization movement to be responsible to notions of settler futurity”.

The Future is illegal. Welcome to the Future!

Since 2012, I had been spending time walking, talking and hanging out along the ruins of the canal, along a stretch that remained forgotten by new development for decades. I met and learned from many different people whose lives bring them in intimate relationship with this place. Native Potawatomie and Cree/Lakota families come here to harvest medicine and conduct water ceremony, re-inscribing native homeland, they say, by renewing relationships with more-than-human relatives. Guerilla gardeners and seed savers come here to look for native tobacco that still grows though 30 feet of settler concrete. Through the cracks you can see the swamp rebecoming itself. The Salvadorian ex-guerilla turned priest and his crew of undocumented families walk in ceremony and protest across here, and a local deaconess conjures a church without walls with every hot drink she hands out nightly from her beat down bus. Girls and families live in tents by the canal, and a handful of aging radicals run a needle exchange. Across the waterway, every morning at 5, migrant workers line up waiting for the local eloteros before being disappeared into vast warehouses. Indigenous folks from South of the colonial border open up a community garden in the shadow of the county jail, complete with community meals, seedsaving, ceremony and a sweatlodge. Squatters tell of living in the grain elevator, of cycles of eviction and return, and of the time dozens were pushed out when the a part of the structure was bombed for visual effect in the movie Transformers. After the dismantling of public housing, and later after the financial crisis, more Black and Brown folks arrive in the tent city. Squatters and street artists return to live in the grain elevator. A trans girl builds a yurt among the ruins where she lives and shares poetry with anyone who knows their way around well enough to find her. Across the canal, a food distro and squat bring together migrants connected to indigenous community self-defense forces in Olinalá, Guerrero, the CRAC-PC and other insurgent indigenous struggles in Mexico. A Mayan mother of 6 puts together a parent/child unschooling coop because I’m not indoctrinating my kids into this colonial bullshit. Puerto Rican mommas move themselves and their kids out of the homeless shelter and start dropping knowledge on how to liberate the boarded up houses that line the neighborhoods up and down the canal. Farther north, families and crusty punks organize an autonomous tenant union, go on a rent strike and barricade themselves in when the police show up to push them out. The whole stretch of canal moves through cycles of resistance, survival, improvisation, refusal. Their dream is our nightmare, a friend sais. The other laughs – The future is illegal, welcome to the future!

By 2014 this place became attractive to developers of logistics centers and server farms, and municipal incentives inaugurated a development boom. Evictions at gunpoint and arrests followed, then fences, surveillance cameras and 24/7 floodlights, with public and private police patrolling the perimeter. Most everyone was pushed out or forced into formal rent arrangements, and some of the mommas were forced to battle for custody of their children. The crusties and yurt-dwelling trans girl moved to La Jungla, another stretch of undeveloped land two miles up the canal, only to get evicted when the high-rise development boom gripped that side of the waterway one year later.

Brian and I organized a series of learning walks through this area in conjunction with a gallery exhibition of our project in 2014, after the evictions had started. Our route took us from the exact location where the canal was first excavated, following the path of the buried canal through landfill born as property, to the ruins of a grain elevator, across an erased continental divide, along disused train tracks to the county jail. We called this a Walk of the Divides. In retracing the making of all the elements in Seamon’s origin story — canal, grain elevator and futures exchange—we were retracing a system that did much more than move grains into storage for later sale: it created the foundation for moving the future envisioned by the settler financiers into the present, and making it available for those with the power to organize that transaction. We hoped this pathway could teach us about the abstract calculations of finance and the bodies, territories and relations that underlie it.

I worried about encountering this as an unpeopled place into which to bring visitors for a tour, an aesthetic experience or pedagogical experiment. This was, to my mind, a rebellious place, and also the most vibrant intellectual milieu I had even been part of. It would not be amenable to the imperatives of so-called activist art or social practice – whereby the social is defined strictly within the sphere of settler legality. I didn’t think neoliberal models of social art practice could account for the collective power and intelligence of people who inhabit the city on the other side of property law; for the wisdom of trespassers, squatters and home liberators, for the sophisticated relationality of community self-defense beyond and against the law and its apparatus; for the ongoing assertions of indigenous relations to place. I was also weary of the ways art has been used in liberal forms of social movement organizing in Chicago, predominately as a form of de-escalation, as a social intervention deployed upon populations seen, from the perspective of the art markets, as in need of correction – or more radically, as the companerxs with Semillas Autónomas charge, as a kind of counter-insurgency, which is how they understand the NGOisation of struggle politics. Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s notion of governance is helpful in theorizing what many of these companerxs recognize well, the patterns of prospecting communities in resistance for the affinities, associations and social innovations they are producing[16]. The extractivist techniques of governance are precise and all too painfully familiar.

But illegalized peoples and squatters and autonomous self-organized migrant collectives would be well equipped to strongly push back against those tendencies; and whatever walks we hoped to experiment with would have to be unpermitted and illegal events. I took heart from the combination of these factors. We proceeded.

One of the walks was “public”, by which I mean we announced it through the gallery where the project was being exhibited. We also assembled longtime artistic collaborators from the Compass group together with some of the ex-squatters and crusties to walk and explore together. For another iteration we organized a walking seminar for a group from El Centro Autónomo, a Zapatista solidarity social center that runs an intensive summer program on social movement histories on both sides of the colonial border. Kara, the rebel yurt-dweller, was our host and guide; it was her last week before being evicted.

After the end of the art exhibit I kept revisiting this same pathway with people from networks of eviction resistance and autonomous migrant organizing. It became something of a local custom, a way to reconnect and bear witness to the ongoing transformations and excavations of the zone, to remember, to celebrate, to mourn. We sometimes worked with companerxs from Semillas, who would invite out of town delegates from different indigenous struggles to this pathway as their first encounter to the city. We put together an exhibition and pop-ed workshop about the histories of the swamp in a new squat just north of the canal, affectionately known as Swamptepec. Janie Pochel and I collaborated along the same pathway, this time walking with a group from the alternative Puerto Rican high school, together with their teacher, an Afro-Caribbean musician who was teaching a class on anticolonial histories of medicine. Local illegalized activists wanted to do a walk as part of a community event and discussion on the War on Drugs and its effect on indigenous communities in Mexico. A new warehouse was being built in the part of the canal zone now under redevelopment. We befriended the workers, and they took us into their worksite where they discovered, to their amazement, the swamp beneath the city.

Our last two attempted visits were in mid-2017, but private police chased us out before we could follow the customary pathway. A fresh new layer of 3 or 4 feet of concrete covered all that was familiar; turf grass and a strip of “decorative landscape” dotted the entrance to the newly-developed complex. A massive data center expansion enclosed the area around the grain elevator. The water was once more being put to work, pumped from the canal to power the cooling fans of the data center, and cycling out again into engineered pools surrounding the building. Construction on the new FedEx distribution complex was completed; hundreds of semi trucks poured through the site along new roadways that now sat on top of the buried canal.

The story of Chicago is the story of the making of this canal zone, the making and making opaque of settler property regimes, so as to appear inevitable in retrospect. The unfinished embattled space of occupation as “safe passage”.

The only space our bodies could take up was on the sidewalks of the public park across the street, one of Chicago’s many “prairie restoration” projects, perched awkwardly on top of 10 feet of topsoil on top of 30 feet of concrete on top of the swamp. A public artwork, made with “at-risk” youth, adorned the park, complete with narrative panels and bas-relief sculptures retelling the glorious story of the canal and Chicago and the grain traders as destined by Geography. The ruins of the old grain elevator were still standing, but now merely a background to the newly developed data center – the calculative machine based on storing seeds now replaced by the protocols and physical infrastructures of hi-speed networks. Pathways that had been opened up by illegalized survival and rebellion, by tent city and street art, by gathering, ceremony, communing, drifting and learning together have once more channeled into the imperatives of trade and capital. Trespass and illicit wandering seem to have been successfully stopped. Lifeways, relations and legal orders that precede, and supersede, the logic of the settler metropolis have been erased. The swamp has once more been subdued. For now.

[1] J. W. Putnam. An Economic History of the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 17, No. 5. The University of Chicago Press (May, 1909), pp. 272-295.

[2] Lisa Guenther, “Chicago Trades Up”, Country Guide, April 25, 2014. online https://www.country-guide.ca/2014/04/25/chicago-trades-up/43835/[3] Mark Rifkin, Settler Common Sense. Settler Colonial Studies, 2013. Vol 3, No 3-4. See also the introduction to Rifkin’s book Settler Common Sense. Queerness and Everyday Colonialism in the American Renaissance

[4]My shorthand definition is indebted to Dick Bryan and Michael Rafferty in “Financial Derivatives as a Social Policy beyond Crisis”. Sociology, 2014, Vol 45(5). p887-903

[5] Randy Martin. Knowledge LTD. Towards a Social Logic of the Derivative. Temple University Press, 2015

[6] Brian Holmes. The River and the Steersman. http://threecrises.org/the-river-and-the-steersman/

[7] See. The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents. Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791 : the Original French, Latin, and Italian Texts, with English Translations and Notes. (Vol 58, p 105) Cleveland:Burrows, 1897. Print.

[8] Other lands adjacent to the canal were made available for sale in the present and purchased by east coast speculators, who bought and sold parcels many times over.

[9] Please see the writing of Métis artist Dylan A.T. Miner, “Makataimeshekiakiak, or the Specter of Indigenous Liberation” in Recollecting Black Hawk, edited by Sarah Kanouse and Nicholas Brown. This book is an important account not only of the significance of indigenous anticolonial resistance and resurgence across the Great Lakes, but also a confrontation with the ways in which settler placemaking negates Indigenous presence and self-governance at the same time as it “appropriates its images and narratives of resistance”.

[10] J. W. Putnam. An Economic History of the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 17, No. 5. The University of Chicago Press (May, 1909), pp. 272-295.

[11] Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler, Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder (Routledge, 2009)

[12] Megan Bang, Lawrence Curley, Adam Kessel, Ananda Marin, Eli S. Suzukovich III & George Strack (2014) “Muskrat theories, tobacco in the streets, and living Chicago as Indigenous land”, Environmental Education Research, 20:1, 37-55, DOI: 10.1080/13504622.2013.865113

[13] H. Davis and Zoe Todd. “On the Importance of a Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene”. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 16 (4). 2017[14] Kyle P Whyte. “Indigenous science (fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral dystopias and fantasies of climate change crises”. Environment And Planning. Volume: 1 issue: 1-2, page(s): 224-242, March 2018

[15] Ena͞emaehkiw Wākecānāpaew Kesīqnaeh. “Whose Land? The Trials and Tribulations of Territorial Acknowledgement”, online at https://onkwehonwerising.wordpress.com/2016/10/18/whos-land-the-trials-and-tribulations-of-territorial-acknowledgement/

[16] Stefano Harney and Fred Moten. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. New York. Minor Compositions. 2013.